He

stands under the oak-bush and waits

The lame

feet of salvation; at night he remembers freedom

and

flies in a dream; the dawns ruin it.

Robinson

Jeffers, "Hurt Hawks"

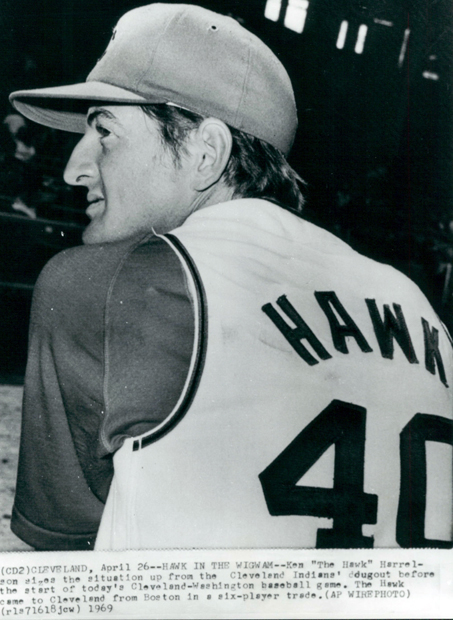

It was 45 years ago today that the Hawk was set free.

Charlie Finley, a meddlesome owner if ever that was, took a break

from firing and rehiring manager Alvin Dark over a Kansas City Athletics player

revolt to give Ken Harrelson his unconditional release on August 3, 1967.

The Hawk, at the time, with an .832 OPS and 147 OPS+ in 61 games,

was K.C.'s best hitter.

Then, a trumped-up episode on a commercial flight, involving supposed

drunkenness from three players (Hawk not included) resulted in a report filed

to Finley from broadcaster/team spy Monte Moore. Finley, no debonair

practitioner of the finer things himself, was nonetheless outraged by this

half-story and announced that no A's would be served alcohol on any future

flights. The clubhouse was up in arms over such fire-breathing restrictions,

and a team statement was released in response to Finley, which got Dark in hot

water (Finley believed Dark was behind the team statement, when in truth he was

unaware of its release).

After Dark's firing, Hawk--a little bristled up, as you might

imagine--told a reporter that he felt Finley's actions were detrimental to

baseball (pretty inarguable, that). Harrelson was also misquoted as calling

Finley a "menace to baseball" (probably not far off, but something

employers don't usually want to hear).

Finley, in typical rash fashion, chose not to trade or waive

Harrelson, moves that would have netted his club players or cash in return. No,

the hotheaded owner gave Hawk a taste of free agency, in a sense, with an

outright release.

Harrelson got to choose from several contending teams pursuing his

services (including the Yomiuri Giants), and as anyone who watches Chicago

White Sox broadcasts knows, he chose the Boston Red Sox. Hawk would play

somewhat sparingly as the Red Sox fought their way to the 1967 AL pennant but

had a key RBI in the pennant-clincher on October 1. Later that month, he would

get his only World Series experience (four games) in Boston's crushing loss in

seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals.

In 1968, Hawk had a monster year for the Red Sox, finishing third

in MVP voting, earning his only All-Star selection, and leading the AL with 109

RBI. His OPS of .874 and OPS+ of 155 were career-best marks, and his 4.6 WAR

that single season essentially represents the sum value of his entire career.

Between the senseless release from Kansas City and confirmed

success as a major leaguer in Boston, it seems something clicked in the Hawk.

He'd finally learned how to be a pro, and he wasn't going to let anything hold

him back from there. He took the unheard-of freedom (a so-called "sneak

peak" at free agency that would arrive in baseball eight years later)

allocated by Finley and made it work phenomenally for him. After badly breaking

his leg sliding into second in 1970, Hawk would lose his passion for the game

and play in just 69 more contests, quitting the game three years into his

Cleveland Indians tenure to pursue a career as a golfer.

He did come back to the game some four years later, broadcasting for the Red Sox, and is now a mainstay of the White Sox organization as booster and critic alike--colorful either way. And to think, if not for Finley rashly cutting him loose 45 years ago, the Hawk might just be hustling pool or scratch golfing instead of entertaining hundreds of thousands every night.

No comments:

Post a Comment